- Home

- Dylan Tomine

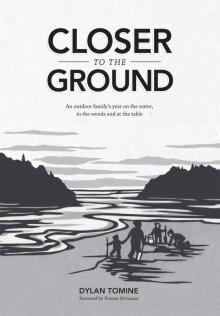

Closer to the Ground Page 11

Closer to the Ground Read online

Page 11

KINGS OF SUMMER

It always comes as a surprise. One day in late August, you look up from the hectic blur of summer activity and realize that things are winding down. It might be a blue-sky, 85-degree afternoon, but something in the angle of the light, or a single falling alder leaf, tells you the season is waning. Autumn is right around the corner.

Fishing for king salmon has slowed over the past week, most of the fish having moved through the Sound and into their rivers. Yesterday we fished for eight hours without a bite. The day before, one small fish all day. It’s been a good season: We’ve eaten fresh kings several times a week, there are bins of smoked salmon in the fridge, and most important, the freezer’s full.

To be honest, even though I look forward to king season all year, the end is kind of a relief. The early wakeups, the long days on the water, the late-night boat cleaning, the constant vigilance over weather and tides take a toll. I’m tired. My back hurts and my hands are wrecked from saltwater and sun. We’ve been rolling on at a crazed pace since the middle of July.

For our family, king salmon season is what deer season is to other rural families: an all-hands-on-deck effort to secure the year’s main protein source. While I’m out on the water, Stacy shoulders the burden of managing both the garden and two energetic children. Then there’s work. Every year, I try to clear the calendar for July and August, and every year, inevitably, writing projects pop up and I have to juggle deadlines with prime fishing times. I feel fortunate to have the work (the mortgage needs to be paid), but for these months, it’s one more factor in the madness.

So, as the season comes to a close, there is relief, but also a touch of melancholy. The end of king season also signals the end of summer. All those warm, sunny afternoons and 10:00 p.m. dusks; the camping trips and barbecues; the bike riding and beach splashing – how did they get by us so quickly? The longest days of the year pass faster than the others.

Silver salmon should be here soon, along with blackberries to pick. With the first autumn rains, chanterelles will push up through the damp forest floor. The best weather of the year – Indian summer – is still weeks away. But a sense of urgency descends upon us with the lengthening shadows and earlier nights. Soon, it will be time for kids going back to school, soccer practice, swimming lessons. For regular bedtimes, early dinners, and catching up on work. For schedules set by forces other than wind, sun, and tide. And at the back of my mind, even though it’s a long way off, I’m already preparing for winter.

But first, one last day of king fishing. Or rather, one last weekday on the water with Skyla and Weston before school starts. King season is technically still open, but we’ve spent most of the summer trolling, and last week, Skyla reminded me again that what she and Weston “really like is to hold the rods.” So today we’ll drift bait for flounders and sharks. We won’t eat them, though. A century’s worth of accumulated industrial pollution in the Sound makes year-round bottom dwellers less than ideal for human consumption. This will be a strictly catch-and-release affair. And while the kids are committed catch-and-eat anglers, they’re still excited to hold the rods, feel the bites, and reel in the fish themselves.

Our day together also buys Stacy some uninterrupted garden time. Although blight may have taken out the tomatoes, the rest of the garden is in full swing. There are weeds to pull, beds to water, and beans, cucumbers, zucchini, beets, carrots, and squash to pick. The pressure canner, vac-sealer, and dehydrator won’t be put away for a month. It’s harvest time, and she’s in full production mode. A day without her junior assistants will increase efficiency.

Since we’re committed to a bottom-fishing expedition, there’s no pressure to be on the water at first light or for a certain tide. The kids and I sleep in, eat a leisurely breakfast, putter around the yard, and put the boat in the water at the public ramp. We run south out of the harbor, then make a big, looping turn back to the north once we’ve cleared the shoals. The air is dead calm, the surface of the Sound a broad sheet of unrippled blue silk. With our light aluminum skiff, it’s a rare day when we can go full blast. Weston shouts, “Go faster, Daddy!” I twist the throttle wide open, the bow drops, and we shoot forward like an arrow.

There’s only one other boat off the point, a couple of old guys trolling for kings in a vintage Whaler. We coast in alongside to set up for our drift and get a report. “We’ve been pounding it since 4:30 this morning without a bite,” the driver says. They continue on their troll and we lower our baits to the bottom. The flounders and dogfish are biting. Both kids stare intently at their rod tips, feeling the bites, hauling back and reeling furiously to see what’s on their lines.

Weston pulls a flounder over the side, and as I’m unhooking it, Skyla says, “Dad, they have a fish on.” I stand up just in time to see the old guys lifting a big slab of writhing chrome into the Whaler. King salmon. A good one. Five minutes later, they’re hooked up again. I’m starting to rethink the whole flounders and dogfish thing, but the kids are enjoying themselves, so we stick with it. But now I’m watching the Whaler like an eagle.

When the old guys put a third king in the boat, Skyla says, “I think we should troll.” With flounders and dogfish forgotten, we hastily rerig for salmon. “You sure you guys are okay with this?” I ask. “You won’t be holding the rods anymore.” Skyla looks at Weston, gets a nod, and says, “We’d rather try to catch a king salmon.” I put the rods in their holders and start the motor.

But we don’t catch a king salmon. An hour passes. The guys in the Whaler boat a fourth king for their limit and start packing up. As we putter by, Skyla whispers, “Ask them what they’re using.” I ask, and the driver answers, adding, “You just gotta put in your time. We fished seven hours before our first bite.” Then they crank up their motor and roar off toward town.

Another hour passes. Weston, having announced he is ready for his nap, curls up on the floorboards and falls asleep. Skyla keeps a fierce watch on her rod tip. The sun broils all of us. “You want to go back to flounder fishing?” I ask. She shakes her head without looking away from the rod. “You want to go home?” Another head shake. “It’s really hot out here,” I say. “Maybe we should head in.”

“Dad,” she says, impatient with me. “We just have to put in our time…”

Well, okay then. Skyla helps me check the gear and we continue on. With no wind – or salmon – to deal with, and the kids content, I let my mind wander back through the season.

Opening Day – just six weeks ago – up at Port Townsend, our annual multifamily camping trip to kick things off. Anticipation ran high with the whole season stretching out ahead of us. After a long afternoon of setting up tents, stacking firewood, and organizing camp, Stacy suggested that Sweeney and I go fishing. There was a stiff breeze out of the northwest and a lousy tide, but we put the boat in the water anyway. Out on Midchannel Bank, the wind whipped around us and a vicious chop made fishing nearly impossible. The boat rocked and pounded, floundering in the waves. Minutes after I asked Sweeney if he thought we should be worried about safety (his answer: “Possibly”), the portside rod hammered down. In less than an hour we hooked five big, ocean-fresh king salmon and put four in the box for a ridiculously quick limit. When we pulled back into camp, Stacy said, “What did you forget?”

A week later, my mom came to visit. Stacy was busy in the garden, and the heat made cooking dinner indoors less than appealing. A little picnic on the water sounded perfect. The fish had yet to arrive here locally, but I figured we might as well drag some gear around while we ate. About a mile south of Kingston, where the bottom slopes up from 150 feet to less than 80, we were busy watching an osprey hunting along the shoreline when I happened to glance at the rod. It was shaking furiously and I knew right away our gear was dragging bottom. I grabbed the rod and felt solid resistance. Dammit. Hung up on a snag. Just as I threw the motor into neutral, line started peeling off the reel and…fish on! The kids took turns fighting the big king – their first ever – and my mom

got to be part of the excitement. When the fish came aboard, we all hugged and danced around the boat. As they say, better to be lucky than good.

I think of the early morning trip with Smarty, when he was supposed to be at work by nine and we’d fished too long. On the way back in, he was frantic, running the boat wide open, skipping from one wave top to the next, asking for the time every three minutes. Halfway across the big open stretch south of President’s Point, he said, “I just lost the steering.” “What?” I yelled, thinking I must have heard wrong. He looked back at me and spun the wheel around several times to demonstrate. The boat kept going straight. And fast. But he refused to back off the throttle – this being the middle of king season, he was already on thin ice with his boss. We somehow made it across the Sound, into the harbor, and right up to the dock by dragging a five-gallon bucket on alternating sides of the boat to steer. He made it to work on time, too, but I’m pretty sure my arms are several inches longer from hanging on to that bucket handle.

And there was the long run up to Possession Bar with Scott Orness, when the incoming tide stacked schools of herring up against a big underwater ledge on the west side. The baitfish (and the salmon feeding on them) were 200 feet deep. To reach them in a ripping current, we had to put out so much line we couldn’t turn the boat without fouling the prop. A rising crosswind made it even worse, and we were reduced to fishing one rod on the upwind side of the boat. When we finally hooked a fish, a seal grabbed it right away and ran for the horizon. Our only hope was to stay directly on top of the seal, forcing him to let go of the fish if he wanted to surface away from the boat. The tug-of-war lasted more than thirty minutes. Every time we thought we had him corked off, he’d shoot out to the side, come up for a quick breath and go back under. Eventually, though, we wore the seal down, and when he opened his mouth, the fish shot straight for the boat and into our net.

And just last week, when Skyla started our fishing day by saying she wanted to see porpoises “in real life.” With this new priority, we spent the day fishing places out in the open Sound, where salmon had been scarce but the porpoises, both the small, dark harbor porpoises and the larger, black and white Dall’s porpoises, tend to feed. It was flat calm and I thought finding them would be a cinch. But hours passed and we didn’t see a single dorsal fin or plume of blowhole breath. Finally, I told her we might as well forget porpoises and just concentrate on trying to catch a fish. We ran to the back of a small bay where fish had been holding and started to troll. Skyla was distracted, scanning the surface for porpoise fins instead of watching her rod. “You can relax,” I said, “they won’t be way back in here. Let’s just fish.” Of course, minutes after I spoke, two sleek black forms materialized behind the boat, came up alongside and kept pace with us. Porpoises. Here? They splashed and swam upside down, weaving back and forth under the boat while Skyla leaned over the bow rail squealing with delight. I was about to say this never happens, but didn’t.

“Dad,” Skyla says, calling me back to the present, “there’s seaweed on both lines.” Lost in my mental slideshow of summer highlights, I’ve driven us right through a tide rip full of eel grass and sea cabbage. She’s right: Both lines are fouled. Skyla cranks the gear up, using both hands on the reel handle, and I lean over the side pulling handfuls of vegetation off our gear. Weston sleeps through the whole process. The sun, directly overhead now, roasts us. I realize I’ve forgotten to bring sunscreen. Both kids have pink cheeks, and Weston, the fairer of the two, is flat on his back, face to the sun. Bad dadsmanship. I pull Skyla’s hat down lower on her face, drape a sweatshirt over Weston’s head and hope for clouds. When we’re clear of the weeds, we put the gear back down and resume fishing.

Another hour passes. Weston sits up, pulls the sweatshirt off his head, and with sleepy eyes and red face climbs onto my lap to wake up. I breathe in the clean, sweaty-head, sleeping-kid smell of his hair. Funny, the things you come to appreciate. “I’m hungry,” he says. “Me, too,” Skyla says. So am I. “Okay,” I say, “let’s head in and grab a snack in town on the way home.” They both shake their heads. “What else did you pack in the ice chest?” Skyla digs out the last, sad-looking salmon sandwich, partially flattened by the ice pack, and tears it into three pieces to share. It tastes wonderful.

Maybe it’s my hunger, or the sandwich itself, but I can hardly look back through the season without reliving the great meals we’ve eaten. As John McPhee wrote of king salmon, “Their dense, ruddy flesh – baked, smoked, or canned – is one of the supreme gifts of nature.” Indeed. I think of the thick early-season male fish, the bucks, heavy with fat and perfect for salt-broiled shioyaki. And the females, the hens, already transferring body fat to their eggs, making them much better brined in salt and brown sugar and smoked over vine maple. Every time I cranked up the smoker this summer, the savory aroma spread through the woods, and neighbors seemed to drop by a little more often.

The deep red, translucent salmon eggs themselves are even better. I push them through quarter-inch hardware cloth to separate the individual eggs, and then rinse them quickly in saltwater. They cure in a little soy sauce, rice wine, and sea salt for about three days, and then I freeze them in small jars. I try to save these cured eggs – ikura – for special occasions, but usually end up eating them right away. We savor them over rice or on crackers with cream cheese, or, as Sky-la and Weston prefer, simply by the spoonful. Skeptical friends, wary of eating “bait,” are quickly converted upon first taste, and it’s tough to build up any kind of surplus in the freezer.

I’m not sure if it’s genetics or personal taste, but for our family, and Skyla in particular, there is a deep preference for the oiliest, fishiest parts of the salmon. When everyone else is eating choice center-cut fillets or steaks, she requests the collar, or kama, as my grandmother would call it. This cut consists of the bony plate behind a fish’s gills and the front pectoral fin socket. Eating it requires the patience to dig through and disassemble the intricate bone structure to find tender, oily morsels within. I usually brine the collars with a batch of fish headed to the smoker, then throw them on the barbecue until they’re crisp on the outside and dripping melted fat. Skyla likes to sit down to a big king collar hot off the grill and a steaming bowl of rice; with each bite, she closes her eyes and chews slowly, chuckling to herself with pleasure. When one of her school friends once watched her eating a collar and exclaimed, “That’s gross!” Skyla replied between bites, “That’s not gross…that’s kama. It’s the best.” Add crisp, tart, thin-sliced garden cucumbers from the garden, marinated in rice vinegar and mirin, and sprinkled with toasted sesame seeds for contrast, and I’m right there with her.

With the lower fat content of late-run fish like the ones we’ve been catching the past few weeks, we favor cooking methods that either add fat or preserve moisture. If we’re having a party, we’ll make what Skyla calls bacon-wrapped yum-yums. I slice the salmon into boneless one-inch cubes, wrap them in bacon, and marinate them overnight in teriyaki sauce. We’ll skewer these and grill them over hot charcoal until the bacon crisps and the teriyaki caramelizes, leaving the salmon medium rare. When it’s just the four of us, we roast fillets in foil or parchment pouches with butter, parsley, garlic, and lemon. For a side dish, the kids dig small red potatoes from the garden and Stacy makes mashers with sour cream, butter, and chives. Then the familiar debate: Crisp, lightly-steamed bush beans or sweet, second-growth broccoli? Often we go with both.

And this brings me back to the sandwiches. I take any leftover cooked salmon and mix it with mayo, a squeeze of lemon juice, dill, and cracked pepper. Sliced wholegrain sourdough from the local bakery, buttered and sprinkled with garlic and grated Parmesan cheese, goes into the broiler. When it’s crisp on one side, I take the garlic bread out and spread a thick layer of the salmon salad on top, followed by lettuce, thin slices of fresh cucumber, red onion, and tomato, and a light dusting of kosher salt. It’s a sandwich I could probably eat every day for the rest of my life.

> It’s been a good season, full of small miracles and memorable meals. A great season, really. And all the days we’ve spent on the water this summer will come back to us in the fall, winter, and spring with each fillet we take from the freezer. Looking at the kids in the late afternoon light, I hope that someday they’ll share summers like this with their own children.

The prospects for the future, though, are not bright in Puget Sound. Wild king salmon are in grave danger of extinction, and the hatchery runs created to replace them are not sustainable. The plan to improve on Mother Nature is backfiring because of the simple fact that hatchery salmon, raised in a perfectly controlled environment, hand fed, and protected from predators, never undergo the all-important process of natural selection. Weak genetics are passed on and amplified, and each year the fish return in fewer numbers and smaller sizes. Fifty years ago, the average Puget Sound king salmon weighed nearly 25 pounds. Today, the average weight is about 12. And an overwhelming majority of recent scientific studies show that the very presence of hatchery fish exacts a terrible toll – through competition and “genetic pollution” – on the few remaining wild salmon.

Our family’s fishing is entirely dependent on hatchery fish. We are required by law (and conscience) to release any wild fish we happen to catch, and still their numbers are low enough to warrant a federal Endangered Species Act listing. The factors causing this decline are human. We are the enemy, and I don’t think we’re going away anytime soon. Industry, population growth, development, resource extraction, and runoff from failed septic systems, car leakage, and lawn chemicals combine to make Puget Sound a tough place for salmon to survive these days.

Closer to the Ground

Closer to the Ground