- Home

- Dylan Tomine

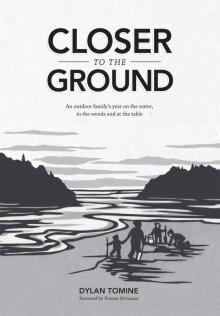

Closer to the Ground Page 4

Closer to the Ground Read online

Page 4

The season has begun. From here on out, we wait, keep up with the work, and watch what unfolds. Looking at these small plants, I find myself guardedly hoping for a bountiful harvest this summer. The rest of the family expects nothing less.

THE SIGNIFICANCE QF BIRDS

I’ve already buried two wedges in the gnarled old fir round, and now my ax is stuck. Only one wedge left. I give it a couple of hard shots with the sledge and stop, hands tingling and ears ringing from metal-on-metal impact. The sun is finally burning through the marine cloud layer, raising an eerie ground-level mist from the damp soil. The woods come to life with birds: towhees, chickadees, wrens, kinglets, sparrows.

In the spring of my junior year of college, my best friend almost died. It was intentional, self-inflicted, and not quite successful. But it was close. And I found myself unable to grasp how something like this could happen, as they say, out of the clear blue sky.

When he was released from the hospital, we sat on the curb outside the entrance, waiting for our ride. It was April and a resurgent sun warmed the earth. The air was sweet with blooming flowers. Small birds filled a tree across the road, chattering and hopping from branch to branch. What, I wondered, could be more benign, more hopeful than this?

“Why did you do it?” I asked.

“It’s spring,” he said in a distracted monotone. “The birds are singing.”

“Yeah…?”

“I can’t hear them anymore.”

A year later, also in April, I was living overseas when his mother called. He’d finally succeeded. The service would be in three days… Could I be there?

When we carried him from the hearse to the graveyard, the late afternoon sun hurt my eyes and the lawn glowed radiant green. I could see each blade of grass in sharp relief. A flock of blackbirds swooped overhead, flaring and shifting direction in unison like a school of baitfish before settling in trees along the path. I was thankful then, and more so with every passing spring, to hear the birds and feel the season.

SPRINGERS

“Wait until the dogwoods bloom,” the old-timers say. But it’s not easy. Pointless as it is, you spend long winter nights poring over notes from last season, plotting and planning. You have to do something while you wait. Then, sometime around Valentine’s Day, scattered reports begin filtering up from the Columbia River – a friend of a friend got one at Kalama, someone else saw a guy with one at Cathlamet – and before you know it, you’re tying leaders and working on the boat, months before it’s even worth going.

Springers do that to you. Maybe it’s the opportunity to chase the first migrating salmon of the year, or time on the water with fishing buddies you haven’t seen since October, or the thrill of big fish in heavy spring currents. Those are all good reasons, but for me, the real motivation is the eating. There is simply nothing – not lobster, not filet mignon, not foie gras – I’d rather eat than fresh Columbia River spring Chinook. Springers are the Kobe beef of fish, aquatic bacon, chrome-plated sticks of salmon-flavored butter… A recent nutrient analysis showed that while the better-known (and highly marketed) Copper River kings weighed in with a whopping 18 percent fat content, our Columbia fish beat them – and any other wild salmon – with a luscious 22 percent. No wonder our family prizes springers above all other foods.

Once, a close relative, who shall remain unnamed, came to visit and slept in the room that also happens to house our chest freezer. At some point during his stay, tired of the compressor keeping him awake, he unplugged the freezer, intending to reconnect it in the morning. Only he forgot. By the time I discovered what had happened, everything in the freezer – most notably our last two springer fillets of the year – was a total loss. That I could barely bring myself to speak to this person for more than a year shows just how much we cherish these fish. Or, what a jerk I am.

Columbia springers enter freshwater from the Pacific in March and April (hence the name), and many won’t spawn until seven months and nearly 700 miles later, way up in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho. Through the entire length of their arduous migration, springers do not eat, meaning they start out larded with more fat than a feedlot hog. For the original people of the Northwest, spring Chinook arrived packed with ocean nutrients just as the long, lean winter was ending, providing the most decadent meal of the year when it was needed most. For this, springers are celebrated with the greatest reverence by Native Americans throughout the region. Though these fish are obviously less critical to our survival, we nevertheless feel similar emotions about them. Springers mean more, and taste better, than any other fish.

Even cleaning one is different. Your hands become slick with grease, as if you’ve been wrist deep in a can of lard. The belly walls are nearly as thick as the shoulders, and the firm, red flesh is richly marbled with layers of white fat. An inch-thick steak, salted the day before and placed on a blazing hot grill, shioyaki style, produces the ultimate salmon-eating experience. Or, in my opinion, the ultimate eating experience, period. The skin and outer flesh crisp in the fish’s own sizzling fat, locking in moisture and creating a buttery, almost omelet-like texture on the inside. And you’re free to indulge without guilt. All that tasty, dripping fat comes loaded with heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids.

It’s no wonder we start dreaming about springers way too early. Frustration builds and you have to resist the pull of the big river when you know the chances are too slim to rationalize spending the time and money. If you’re lucky, you still have some left in the freezer from last season. Vacuum-sealed and frozen, a big fillet can keep for months—as long as nobody unplugs the freezer. Or maybe you have one more bag of smoked springer bellies stashed away behind the last jars of freezer jam.

Eventually, the long wait comes to an end. Maybe it’s the sudden predawn chorus of tree frogs or the high, reedy whistles and scrabbling claws of tiny red Douglas squirrels chasing each other around fir trunks outside the bedroom window. Or maybe it’s some subtle change in the night air or a faint scent of pollen. But one morning, before you even wake, you know spring has arrived. And that means it’s time to load up the fishing gear and head south.

Sweeney’s has been ready for a month, boat prepped, trailer bearings greased, fuel tanks full. I mention this to point out that I’m hardly alone in my springer obsession. If we were getting paid for time spent on springer-related phone calls and e-mails prior to our first trip of the year, we could retire by the middle of March. Technology only complicates the process. On the Internet, we look at real-time stream flows in cubic feet per second, water temperature, rainfall amounts in a dozen tributary watersheds, river turbidity, and the marine weather forecast. (All of which tell us what we could determine by a quick glance at the neighbor’s dogwood, but that would be way too easy.) What Stacy calls my “pretrip dithering with Sweeney” is, to us, a kind of algorithm that determines success. Sweeney has one pipeline of information, I have another, and we have to put our heads together before making the commitment. After all, it’s a four-hour drive down there and a full day or more away from family and work. But there’s probably a fair amount of dithering involved as well.

Finally, everything lines up. On the drive down, once we leave the interstate and start working our way west, the beauty of the country and season takes hold. Steep, heavily forested mountains plunge to the big river’s edge. Waterfalls cascade down creek beds cloaked in the electric green foliage of new growth. Brightening alder thickets seem to float like pale green clouds between dark stands of timber. It’s easy to imagine how Lewis and Clark, having survived their wet, miserable winter at Fort Clatsop, must have felt when they witnessed this awakening landscape for the first time.

Or 25 years later, when David Douglas, the young Scottish botanist, arrived at Fort Clatsop to catalog the unknown flora and fauna of this newest world. Reading accounts of these early explorers leads to the inevitable – and unflattering – comparisons with our own outdoor experiences. We have become soft. We cringe at the thought of a little wind

chop on the water or being caught in the rain without the latest high-tech outerwear, and find the physical toughness of our predecessors inconceivable. In Douglas’s day, they paddled 30-foot canoes up the Columbia, against the force of unimpeded current, for hundreds of miles, portaging around the Cascades of the Columbia and Celilo Falls. Portages then meant hauling massive canoes, along with all the cargo (conveniently divided into 90-pound sacks), up and around these rocky cataracts on foot. At night, Douglas felt fortunate to take shelter beneath the dripping firs that now carry his name, grateful for the warmth of a single wool blanket that was wet more often than not. Ah, the good old days.

We modern “adventurers” don’t even deserve to carry a guy like Douglas’s daypack. Hell, I doubt we could lift it. On the other hand, the life expectancy of early American explorers was considerably shorter than ours, and even tough-as-nails Douglas himself didn’t live to see his 36th birthday. I, for one, will happily take the tradeoff.

While we may be thankful for the advances in safety and comfort (not to mention longevity) developed in the nearly 200 years since Douglas walked these shores, there is much to mourn as well. On my desk, I have a photo of a Columbia River spring Chinook taken 100 years ago that reportedly weighed 89 pounds. Eighty-nine pounds! Today, the average springer weighs in at around 12, with a really good one going 25. We’re fishing for minnows.

And comparatively, very few minnows at that. In a typical year, the Columbia now receives a total run of about 1.3 million salmon and steelhead combined. Estimates based on cannery records from the 1890s provide a historical “baseline” population of between 10 and 16 million fish. And more recently, research conducted by Bill McMillan, a biologist with the Wild Fish Conservancy, shows that salmon runs prior to the extensive beaver trapping and agriculture of the 1800s (loss of beaver dams destroyed vital habitat, and unscreened irrigation intakes killed millions of juvenile salmon) greatly exceeded the cannery-record estimates.

According to McMillan, to really see what this river was like in its full glory, you have to look back even before Douglas or Lewis and Clark ever set foot here. Then, people of the Cathlamet and other Chinookan Nation tribes lived in a land of unimaginable plenty, the great river nearly overflowing with salmon, sturgeon, smelt and waterfowl. Traditional fishing sites at Celilo Falls and the Cascades of the Columbia attracted tribes from hundreds of miles around and grew into thriving centers of culture and trade. When the first foragers sat down to a meal of fresh spring Chinook, with fern fiddleheads or horsetail shoots and camas root, they had to treasure it even more than we do. And today, their descendants must feel heartbroken over what’s happened to their great river.

The precipitous decline in fish size and numbers starts with the 400-plus dams – two of which buried the traditional fishing sites at Celilo Falls and Cascades of the Columbia beneath massive lakes – built on the Columbia and its tributaries. Together, these structures form the largest hydroelectric complex in the world and generate more than 21 million kilowatts of “cheap” electricity. The cost, though, in terms of salmon, has been dear. Despite the $11.8 billion spent on salmon mitigation, the Columbia’s wild salmon hang by a thread.

It’s not just the dams. Agriculture, heavy industry, and commercial fishing all play a role in the sad state of Columbia salmon populations. Fish hatcheries, built by dam operators as the cornerstone of their mitigation efforts, have instead contributed to the decline. Mass releases of hatchery-produced juvenile salmon out-compete their wild cousins, while hatchery adults pollute the gene pool when allowed to reproduce in the wild. Just another example of man thinking he can somehow improve on Mother Nature, I suppose. When you consider all the catastrophic changes we’ve inflicted on this once magnificent watershed over the past two centuries, it’s incredible that we have anything left to fish for at all. So, in spite of all the losses here, I’m thankful for days like today.

After a quick and hassle-free launching of the boat – our late start does have its advantages, since every other lunatic in the state jammed the ramp long before daybreak – we run downstream and drop anchor on a shallow flat to catch the last half of the outgoing tide. Although they have an enormous river and plenty of deep water in the shipping channels to inhabit, springers, for reasons unknown to us, prefer traveling over shallow sandbars and along the shore. Once the anchor grabs, we cast our gear into the swift current and settle in to wait. And wait. And wait.

A cold east wind pushes downstream, making the boat sway back and forth despite the large sea anchor hanging off our stern. Squalls pour down from the Columbia Gorge, white curtains of whistling wind, pounding rain, and pea-sized hailstones. Sweeney calls the horizontal precipitation “eardrum rain,” because of where it hits you. Last season, our first day of springer fishing saw six inches of snow cover the boat. Spring is a relative term, especially here.

Hours pass. Our early optimism wanes and conversation becomes monosyllabic as we hunch down into our fleece and Gore-Tex parkas. How Douglas survived this with a single wool blanket is beyond me. The old-timer next to us is packing it in. He emerges from the jury-rigged canvas rain fly above his steering console, looks up at the sky and then at us, shaking his head. “Damn east wind,” he mutters, “no good for nothin’!”

“Fifteen minutes,” Sweeney announces, “then we have to troll.” The tide is almost dead low now, with only five feet of water under the boat and barely enough current to work our lures. Soon, the incoming tide will stop the current altogether, and shortly after that, the river will reverse and run upstream, bringing an end to our fishing on anchor. I start putting away the “plunking” gear and take out the trolling rigs. When I look up, my rod is bent to the handle, with line peeling off the reel.

I leap to my feet, grab the rod, and the fish streaks away downstream, then reverses itself and runs toward the boat. I reel furiously, and when I catch up to the fish, it’s about a rod length off the transom, twisting and bulldogging in the current. I pull a little harder, and it comes along, still resisting but moving toward Sweeney, who’s waiting with the net. I envision sizzling springer fillets coming off the barbecue, and in that moment, the fish turns to run again and the line goes slack. My lure wiggles to the surface, empty. The air goes out of me like an untied balloon. “It’s gone,” I say.

“What do you mean, it’s gone?” Sweeney yells. Because of the value we place on these fish, we have a longstanding agreement to share all springers taken, so my loss is not mine alone. And I committed the cardinal sin of eating a fish before it was in the boat. I reel up my slack line, thinking of weak excuses, but can’t come up with any worth saying. “You were thinking about eating it, weren’t you?” Sweeney isn’t asking, he’s accusing.

The current has died now, but the weather hasn’t. We crank up the motor and I inch the boat forward into the chop while Sweeney goes up to the bow to pull the anchor. “You want to bag it?” I ask. “Hell no,” Sweeney says. “You?” “Nope, we’re here,” I say, “might as well fish.” Brave words, but there isn’t a whole lot of enthusiasm behind them.

The other boats in the fleet – no doubt manned by people far smarter than us – are headed for the barn. I can see their wakes through the pummeling rain, peeling off to the left toward the marina. We alone cut right at the top of the island and, running tight to shore, make the turn into the trolling grounds. Here, the wind has a much longer unobstructed fetch, and when it collides with the now incoming tide, the water stands up in sharp, rolling whitecaps. Damn east wind, no good for nothin’.

The boat pitches and rolls, wallowing through wave fronts and surfing down the backsides. We have the whole channel – normally filled with hundreds of boats – to ourselves. We slow to trolling speed. Sweeney grimly tries to keep us on course, while I get both sets of gear in the water. We seem to be fishing, but it’s hard to tell. Between the wind, chop, and fast pace required to maintain steerage, I have no idea what our baits are doing down on the bottom.

“How long hav

e we been trolling?” Sweeney asks. I pull a soggy sleeve up and look at my watch. “About four hours.” “That’s funny,” he says, “It only feels like eight.”

Almost high tide now, and we’re crawling along, crabbed out at a 45-degree angle to the wind. After a long, fishless day, I cling to a shred of hope that the turning tide might change our luck, as it sometimes has in the past. The wind seems to be falling out a little, too. When we pass the abandoned cannery on the Oregon side, I dream of 89-pound springers and the good old days. With just a little squint, the peeling red paint and broken windows disappear, and I can imagine the bustling activity salmon once brought here.

Then suddenly I have a fish on. I try to snap back to the present, but find 100 years of history and a full day of sitting motionless in the cold almost impossible to overcome. My wet, frozen fingers are too numb to grip the reel, and out of desperation, I press the palm of my hand against the handle and crank. The fish somersaults through the chop, pulling hard for the far bank. When enough adrenaline enters my bloodstream to revive my extremities, I work the fish toward the boat with exaggerated caution. When it surfaces just off the port side, Sweeney makes a long reach with the net and brings our springer aboard.

I kneel down to unhook the gleaming silver slab with shaking hands and wobbly knees. Springers do that to you, especially the first one of the year. And the difference between zero and one is greater than the difference between one and any other number. We had to scratch and claw all day, but now we have a fish in the boat, and that makes all the difference in the world.

Now I can safely think about eating it. Properly bled, cleaned, and allowed to “rest” in the fridge for a day or two, this fish will become the meal we look forward to more than any other. You always hear how good fish is “fresh out of the water,” and while that may apply to some species, salmon need time for their flavor and texture to develop. If you cook a salmon fillet right after catching it, you will be disappointed when the flesh curls and contracts and even more so when you bite into its rubbery consistency.

Closer to the Ground

Closer to the Ground