- Home

- Dylan Tomine

Closer to the Ground Page 8

Closer to the Ground Read online

Page 8

The early raspberries – Summits – are getting close, the fruit just starting to turn pink on canes I pruned back in March. But the cool, wet spring slowed things down. Worse, it’s causing the wild salmonberry crop to fail, and hungry birds have turned to our raspberries, cherries, and blueberries to fill their stomachs. I tried “bird proof” netting and they crawled right under it. Flashing Mylar strips did nothing to discourage the feeding frenzy. Finally, I bought a plastic hawk statue marketed to suckers like me as a surefire bird deterrent. I realized it was futile the morning I watched a robin sitting on the faux hawk’s head, calmly munching green raspberries. Like it or not, we are going to have to share.

June-bearing strawberries are safe inside their chicken-wire cages, but faring little better. My scorched-earth pruning technique from the spring hasn’t done them any favors. They just didn’t have enough time to fully leaf out before fruiting, and now, unable to gather sunlight, the stubby plants are producing small, anemic-looking berries.

Stacy’s cool-weather vegetables – broccoli, cauliflower, spinach, chard – are flourishing. No danger of bolting from heat this year. Instead, they have grown thick and stocky, their leaves dark with densely packed nutrients. At dinner each night, these every-day, ordinary vegetables, simply steamed or sautéed, burst with flavor and sweetness far beyond their common reputation. They are the lone satisfaction in an otherwise gray start to the gardening season, and consolation for the sad state of our heat-loving tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant. Looking at another thin, pale tomato plant, Stacy says, “If we can just get another sixty days as nice as today, we might still be all right.” She doesn’t sound very confident, though.

It’s pushing ten o’clock when we go inside. The kids are still wound up, too excited to fall asleep easily. An hour after we tuck them in, multiple drinks of water and trips to the bathroom are required. Later, I experience the same restlessness. It starts with calculations of tide and wind, my brain whirling with crabbing strategies, and gradually devolves into counting the hours of sleep I can still get if I fall asleep right now.

The accelerating bongo riff of Weston’s bare feet pounding down the hallway wakes me from the deep sleep I finally fell into about five minutes ago. Bright sunlight fills the room. “Dad, Dad,” Weston calls out as he charges around the corner, launching himself for a full body slam, “Wake up! It’s time to go crabbing!”

While I hook up the trailer, Weston stands in the driveway, craning his neck to watch a flock of crows polishing off the last of our unripe cherries. Last year, when early spring sunshine produced a bumper crop of wild salmonberries, the birds had little need for cherries, leaving us with more plump, sweet fruit than we could deal with. That’s not going to be a problem this year.

On the far side of the nearest cherry tree, above the squawking crows, I catch a glimpse of tropical color, a bright flash among the dark green of mature foliage. “Weston,” I say, “look up there.” I take his hand and we stalk slowly around the base of the tree, looking up through the dense canopy. The crows pay us no attention. “There,” Weston whispers. A brilliant bird, a little smaller than a robin, with a fluorescent yellow breast and crimson face, perches on a twig. Compared to the subdued colors of our forest and the birds that live in it, this one looks thrillingly out of place. A rare visitor from some steamy equatorial jungle? Escapee from a neighbor’s birdcage?

“What is it, Dad?” It’s disappointing to have to tell him that I have no idea. Since Weston first started talking, attaching names to things has held particular importance for him. He’ll walk down our road reciting plant names – salal, black huckleberry, red huckleberry, bracken fern, sword fern, cedar – and there isn’t a dinosaur in any of the books we have that he can’t name. I have to remember to look it up later so I can tell him what this bird is called. I want to know, too. It’s important.

We put the boat in the water at a small private ramp just up the road from our house. This ramp, owned by the community surrounding it (of which we are not members), has been a blessing for our family, providing quick, easy access to the Sound. Because it’s significantly closer to the fishing and crabbing grounds than the public ramp, we avoid the long, pounding boat rides that can be hard on kids. For years, we’ve used this ramp by the generous permission of friends who live there. Of course, they said, feel free.

When we first moved to the Island, one of my earliest and happiest discoveries was a longstanding tradition of generosity from people who live on the water. It was almost as though waterfront homeowners felt an unspoken responsibility to share the Sound with people who lived inland. If someone were coming to visit us by boat, a friend of a friend would hear about it and loan us her dinghy and mooring buoy without question. When crab season opened one year and we were between boats, a new acquaintance volunteered the use of his skiff. Bob Dawson invites us to dig clams on his beach and tie up to his dock. Smarty says to take his boat if we don’t have time to launch ours, pull his pots if we need crab, come out for spot prawns and bring the kids. Of course, they’ve all said, feel free.

But things are changing at the boat ramp. Despite my best attempts to be a good neighbor (filling holes in the beach made by others, picking up litter, coming and going quietly), some in the community have taken exception to our use. Recently, notes went out complaining about uninvited guests. The combination on the gate lock was changed. The last few times we’ve used the ramp, we’ve been met with suspicious stares and pointed questions. We have become unwelcome.

Our friends who live there assure us they have every right to grant us permission. Another longtime resident said she was happy to see someone taking advantage of the seldom-used ramp. We were told the complaints came only from a handful of new residents, recently arrived from a state where property rights and litigation are the primary concerns of land ownership. Of course, our friends insist, feel free. But I don’t know. The thought of Skyla and Weston witnessing a confrontation – or worse, feeling unwanted somewhere – puts a damper on what should be pure fun. And it’s not like I have any rights here. I hold no grudge against the property owners who wish to keep outsiders away; it is their ramp, after all. If the situation were reversed, I might feel the same way. I am sad, though, for the loss of something that has meant so much to our family, and in a larger sense, for the end of a fine Island tradition.

Today, despite my misgivings, we use the ramp. I park the car and trailer up against the bushes where it won’t be in anybody’s way and skulk back down to the boat with the head-down gait of a trespasser. The kids are already aboard, clipping their life jackets. I start the motor in record time and Stacy pushes us off the beach, leaping over the bow rail. Whew. We are under way, and for now, any thoughts of angry neighbors are left behind.

We run straight out of the little harbor into the open Sound. A faint north wind riffles the surface, and I wonder how much it’ll blow once the land heats up. It’s reassuring to know we’ll be close to the ramp in case we have to get off the water quickly, but with this thought comes a pang of gloom over our access situation. I have to consciously push it from my thoughts. Bearing west, the depth finder shows an upward-sloping bottom that levels off onto a broad flat about 100 feet deep. Smarty likes to put his pots right on the edge of this underwater plateau, close to the drop-off but not on the slope, where gravity might keep the pot doors from swinging closed. I can see his buoys just ahead. We’ll run a couple hundred yards past his string to give him some space and drop two pots; then, to cover our bases, we’ll put our other two a half mile east, in deeper water off the sand spit.

With the season just starting, nobody knows where the crabs are yet. But we do know where they aren’t: anywhere the commercial geoduck divers blasted the bottom apart with their hydraulic hoses. Since they’ve gradually worked their way around the north end of the Island in 60 to 70 feet of water, we have to go a lot deeper than in the past. To find the coveted Dungeness crabs (and avoid the less desirable red rock crabs), we look

for a sand or mud bottom, preferably with eelgrass and as deep as we’re willing to pull pots from. For me, that’s generally between 80 and 120 feet deep. No matter what, it’s going to take some work.

It’s not just the geoduckers who make crabbing tougher these days. With 240,000 recreational crabbers in Puget Sound, plus an intensive commercial fishery, the crabs here survive under heavy pressure. With good bait, good location, and long soaks, we still sometimes fill our legal limit of five male Dungeness crabs per person, but most of these will just barely clear the 6½-inch minimum size. Usually, our haul is something less than the full allotment – sometimes a lot less.

Several years ago, I went up to the north coast of British Columbia to explore the Inside Passage aboard an old converted trawler. My boat mates included Yvon Chouinard, Bruce Hill, Gerald Amos, and other conservationists who had worked to preserve this section of coast, the world’s last untouched temperate rain forest. Our task was to obtain DNA samples from native steelhead for research, which involved – some find this amusing – the high-tech, scientific sampling method of…fly fishing. But the reason I bring this up is that for residents of densely populated areas in the Lower 48, northward travel is a kind of time machine. Go far enough, and the years recede, revealing what used to be. Way up near the Alaska border, I experienced crabbing the way it must have been in Puget Sound 100 years ago.

One day, as the old trawler chugged down yet another spectacular vertical-walled fjord, Gerald Amos, a local Haisla First Nation leader, and I took the Zodiac and motored ahead to a small cove. While Gerald puttered around the calm waters, I baited four crab rings and tossed them overboard into 15 feet of water. When I dropped the last ring, Gerald immediately took us back to the first. Ten minutes had passed. “Pull it up,” he said, a smile crossing his broad face. I figured he wanted to move the ring to a better location, but when I grabbed the rope, I could barely lift it. Still not believing the bonanza I was about to witness, I thought we had hung up on the bottom. Wrong and wrong. I finally wrestled the ring to the boat and it took both of us to pull it over the side. Inside, crabs were stacked four and five deep, many of them bigger than any I’d ever seen. Although we kept only the biggest males, the four rings yielded 57 Dungeness crabs measuring between seven and nine inches across the back in less than half an hour. From water 15 feet deep. It was then that I first grasped the seismic shift that our baselines have undergone.

It was also then that I first understood what it means to be crabbed out. We ate crab three times a day for nearly a week, mostly standing on the trawler deck stuffing our faces and throwing shells overboard. The abundance proved too much for us “southerners,” our senses having adjusted to more austere foraging. By the end of the trip, nobody even wanted to see another crab, let alone smell one cooking. Except for Chouinard, who continued to slurp the pungent, steaming crab innards with great pleasure, passing the meaty legs and claws to others. That trip, 1,000 miles north and maybe 100 years ago, permanently lowered my crab-out threshold.

Back in present-day Puget Sound, with baselines fully shifted, we feel fortunate to find enough crabs for a single meal. It might not be easy, but the process is simple. We bait wire traps, or “pots,” with salmon heads and send them to the bottom. Once there, the heavily weighted pots – ours have three to five pounds of lead holding them in place against powerful tidal currents – attract crabs and employ various methods to trap them inside. The inexpensive, rectangular Danielson pots have a gate on each side that allows crabs to enter and then swings shut behind them. The big, octagonal McKay has two ramps that lead crabs in, where they fall to the floor of the pot and can’t escape. The Ladner, a heavy, round, commercial-style pot made with handwoven stainless steel wire, uses a combination of ramps and swinging wire gates. Each has its benefits and drawbacks, but in general, the easier it is for crabs to get into a pot, the easier it is for them to get out. For short soaks, the easy-in, easy-out Danielsons tend to fish best, while the more complex pots work better left overnight.

Today, we’re moving fast and trying to cover as much ground as possible. We drop the last pot and cut the motor to drift, waiting. Stacy stretches out, lying back against the bow, eyes closed, face turned up to the sun. Weston and Skyla tear through the lunch cooler, eating, chattering, asking if it’s time yet. I keep looking at my watch, willing the hands to move faster. By the time Weston has plowed through his second peanut butter-and-jelly and Skyla has counted 43 jellyfish under the boat, it’s been an hour since we set the first pot.

We motor back to the general vicinity of our first pots – 105 feet of water on a line between the barge buoy to the south and the red, metal-roofed house on the north shore – and start looking. There are lots of other buoys scattered across the bay. Ours, counterweighted to stand up vertically above the surface and topped with bright orange flags, should be easy to see. But they aren’t. I idle slowly through the area until I spot a flag flapping from the top of our first buoy; I edge toward it. “Keep looking, you guys, we need to find our pots,” I say. Stacy sees it, too, but we don’t say anything to the kids. We want them to make the “discovery.”

When we’re almost on top of the buoy, they both start jumping up and down, pointing and shouting. “Skyla, up to the bow,” I say. “Weston, get ready.” Skyla reaches over the rail and grabs the flag. As the boat slides forward, she passes the buoy to Weston, who walks it back to Stacy. Stacy pulls a few arm lengths of slack from the line, unsnaps the buoy, and hands me the line. I remind the kids that we can’t all be on one side of the boat, but they’re too busy leaning over the gunwale, looking into the depths. I step back to balance the boat and haul from the far side.

This first pot, a quick-fishing Danielson, comes aboard with the following: one small orange starfish, three hand-size rock crabs, two smallish female Dungeness crabs, and two big males. Not bad for a fast soak, but it could have been better. Stacy hands our two keepers to Skyla, who confidently carries one in each hand and drops them into a five-gallon bucket. Weston, still a little fearful of the big crabs, gingerly releases the other creatures into the sea and watches them sink out of sight. Now the dilemma: Drop the pot again here or gamble and keep it in the boat until we see how our other pots have fared? The crew votes to roll the dice and keep it aboard.

The second pot, 50 yards to the north, contains a single, three-foot-long dog shark that somehow pushed its way through the crab door and lies curled inside the circular Ladner. Not a single crab. I open the pot lid and carefully grab the writhing shark behind its head and ahead of the tail. The kids feel its rough, sandpaper skin and examine the mysterious, glowing-green deepwater eyes. The shark splashes us with a stroke of its tail when I drop it overboard.

Our pots off the sand spit have been in the water for nearly two hours by the time we reach them, and I’m not sure if it’s the longer soak, the slackening tide, or just a better spot, but combined they produce eight keepers, along with a dozen undersize and female crabs. Or it could be Stacy’s mojo, since she pulled these last two. Whatever the reason, we have stumbled into an unexpected jackpot. We reset these pots and drop the others nearby.

The original plan was to find a decent concentration of crabs and leave the pots to soak overnight. But the first pot of our second round comes up with four more keepers. If the remaining three pots produce at all, we’ll have more than enough. Hello, gluttony. The bucket is already overflowing, and big purple-tan crabs scuttle all over the floorboards. We stow this pot and move on to the rest. When all four are aboard, we have 18 keepers and we’re all moving carefully to avoid stepping on crabs. It feels like we just hit the lottery.

We load the boat onto the trailer, escape the ramp without incident, and on the short drive home, bask in the satisfaction of a big haul. I even manage to back the trailer through the obstacle course that is our driveway – around the cedar stump, inside the big fir, between the rhododendrons – on the first shot. I believe this is what professional athletes refer to as bein

g “in the zone.”

I hook up our propane crab cooker – sold as a turkey fryer in other parts of the country – in the driveway, fill the big pot with water and add salt until it tastes just a little saltier than seawater. I can keep an eye on it while washing down the boat and trailer. I’m also watching the cherry trees for another glimpse of the bird we saw earlier, still wondering what it was and hoping for a closer look.

When the cooker lid rattles, I drop six crabs into the roiling, salty water, hit the timer on my watch, and try to pay attention to my boat-washing duties. It isn’t easy. Every time the breeze shifts, a cloud of fragrant crab steam wafts toward me, and my mouth waters.

Weston runs out of the house carrying our dog-eared Sibley bird book. “Here’s the Sib-i-ly, Dad,” he says. “Can we look up that bird?” I knew there was something I was supposed to remember. We open the book. “Is this it?” I ask. “No…Dad-dy! That’s a mallard.” I flip a few more pages. “How about this?” “That’s a spotted towhee.” I keep turning pages, until finally, “Dad! Dad! There it is. Go back.” It’s as exciting for him to find the mystery bird here in a book (and attach a name to it) as it was to see it live. He’s right. There it is: western tanager. Having never seen one before, I’m a little disappointed to read that it’s considered “common.” No exotic tropical visitor here. Weston, though, isn’t bummed in the least. He says the name to himself a few times, a look of deep satisfaction on his face, then runs back into the house, shouting, “Mom! Skyla! We found the yellow bird!”

The crab cooker boils over, sending a cascade of foam down the side and a more intense blast of crab vapor into the air. I adjust the flame to simmer. We’re almost there. I give up trying to wash the boat and instead stand idle, watching the proverbial pot boil. Five long minutes pass, and then, finally, it’s time. I pull the scalding, brilliant red crabs from the water with barbecue tongs, rinse them off, and set them on the picnic table to cool. Six more live crabs go into the pot.

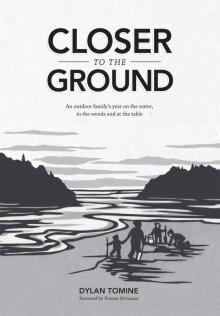

Closer to the Ground

Closer to the Ground